Would you believe it if I told you that French students often start school at 8 a.m. and finish as late as 5 p.m.? That chewing gum is banned in class, and students have little to no choice in their subjects? This is just a glimpse at the French school system, which is quite different from what students in the United States experience.

In France, school begins at the age of three. During the first three years, known as “maternelle,” children learn to sit still, draw, and adapt to the classroom environment. Then comes elementary school, which lasts five years and where they learn foundational skills such as reading, writing, and basic math. The transition to middle school—referred to as collège in French—is a significant step.

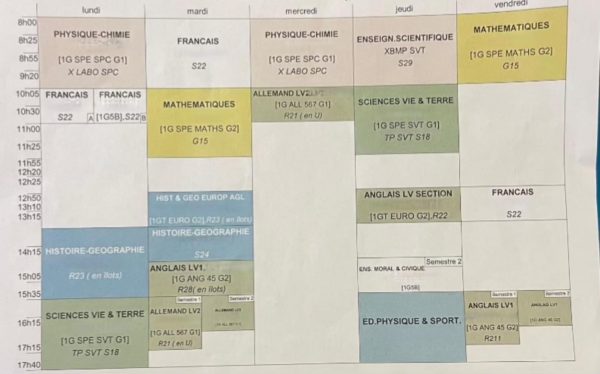

Unlike in the U.S., middle school in France lasts four years, including the equivalent of freshman year in high school. Teacher-student relationships are also more formal in France, with teachers addressed as “Monsieur” (Sir) or “Madame” (Madam), compared to more casual dynamics often seen in American classrooms. Students have a diverse curriculum, including French, math, physics, chemistry, biology, history, geography, English, a third language (often Spanish, German, or Italian), and technology. While physical education, music, and art are included, they are limited to just an hour or two each per week. The schedule is demanding, with classes starting at 8 a.m. and often finishing around 5 p.m., though students do get Wednesday afternoons off. However, this time is often spent catching up on homework or preparing for tests, as French schools assign significantly more homework compared to the U.S.

At the end of middle school, students must pass a national exam called the Brevet, which evaluates their knowledge across most subjects they’ve studied.

High school, or lycée, is where things become even more intense. French high school students often have longer days, sometimes not finishing until 6 p.m. The system places heavy emphasis on standardized exams, particularly the Baccalaureat (exam at the end of high school years), which determines your higher education. This contrasts with the SAT/ACT in the U.S., which are optional and just one part of college applications. High schoolers are also spending weeks, sometimes even months, studying for their final exams. Unlike American schools, there are no sports teams, clubs, or social events like homecoming or pep rallies organized by the school. Students who want to participate in sports or extracurricular activities must do so through outside clubs, which can be challenging with their rigorous schedules.

The French high school curriculum is heavily academic. In their sophomore year, students choose three main subjects to focus on, which they will study in depth during their junior and senior years. By junior year, French becomes a core focus, with students taking a national exam that includes both written and oral components. Senior year replaces French classes with philosophy, and students prepare for the baccalauréat—a series of exams in their main subjects, philosophy, and a final oral presentation. These exams, often lasting four hours each, require extensive memorization of formulas, quotes, historical dates, and more.

French schools emphasize theoretical learning, which contrasts with the practical projects and collaborative work often integrated into U.S. classrooms. Discipline is stricter, with firm rules about punctuality, dress codes, and behavior. If students do not respect these rules, they receive “bad notes” which are recorded on their transcripts and required for college applications. If students accumulate too many “bad notes”, some schools require them to attend punishment hours on Wednesday afternoons or Saturday mornings. Absences and tardies are also all listed in the transcripts. Another notable difference is that teachers move from classroom to classroom, and students stay with the same group of peers for their core subjects throughout the year. Classes can last one or two hours, and the schedule is not fixed—students don’t always start or finish at the same time every day.

The grading system in France is another notable difference. Instead of a GPA, grades are out of 20, with anything above a 16 considered excellent. The standards are strict, and achieving perfect scores can require hours of studying.

Technology is less integrated into the classroom. Instead of Chromebooks or tablets, students rely primarily on paper and pens. Phones are strictly regulated: middle schoolers are not allowed to use them at all, and high schoolers can only use them during breaks, never in class or the cafeteria.

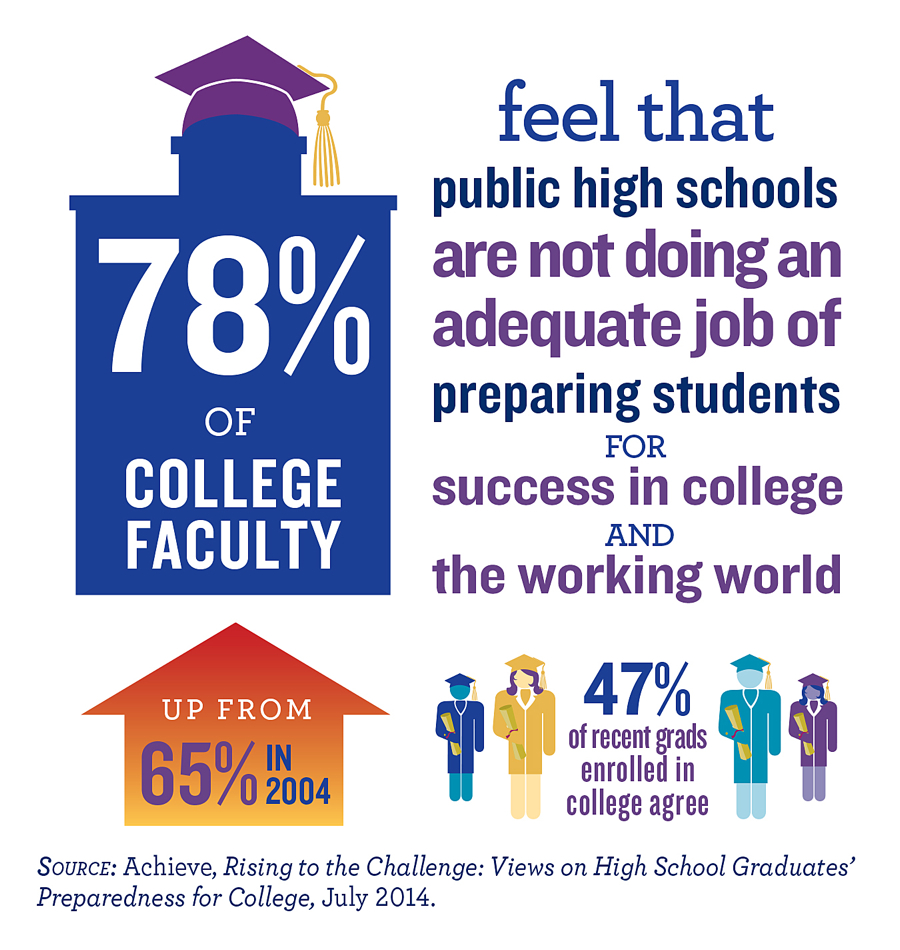

But the French school system has its benefits. It’s designed to prepare students well for college and professional life. The rigorous curriculum helps students develop strong organizational and time-management skills early on, ensuring they are well prepared for higher education.

Lunch breaks last at least an hour, allowing the students to eat hot meals provided by the school cafeteria and fostering healthier lifestyles. Additionally, most high school students stay on campus during lunch since they don’t drive, as the driving age is 17, and owning a car at that age is uncommon.

While the French school year starts in early September and ends in late June, students enjoy several two-week breaks throughout the year—around Halloween, Christmas, February, and Easter. These frequent breaks, combined with a two-month summer vacation, help students recharge despite their demanding schedules.

Finally, higher education in France is remarkably affordable, with tuition fees at public universities being minimal compared to those in the U.S. This ensures that education remains accessible to everyone, regardless of their financial background.

For exchange students like me, adjusting to a new school system can be hard. In my opinion, the hardest part was being with different people in all my classes, making it harder to form close friendships. Using a Chromebook daily in all my classes was another challenge. In France, students do not have personal devices to use in all their classes. We also use different platforms for grades, schedules and homework. Another challenge was typing quickly on a keyboard, especially since French and English keyboards are different. In my first few months, I typed much slower than other students, and even though I am getting better, I am still not as fast. Doing assignments and tests on a Chromebook was completely new for me. In France, all tests, assignments, and even class notes are on paper. The grading system was also an adjustment. I was confused in my first few days because, in the U.S., everything is graded–quizzes, small assignments, and even group activities. In France, only tests are graded. We still have a lot of homework and assignments, but they are meant to practice rather than grades. Teachers check that we do them, but the goal is learning, not assessment. Another major difference is that in the U.S., students are often allowed to use notes during tests, whereas in France, we must memorize everything, sometimes excessively.

Both systems have their strengths and weaknesses, but the differences highlight the cultural priorities of each country. Whether it’s the focus on academics in France or the balance of academics and extracurriculars in the U.S., each system prepares students in its own way for life beyond school.